By Jaleen Grove

It’s not every day that a Canadian illustrator gets a solo show in New York. Especially a deceased one that few know about.

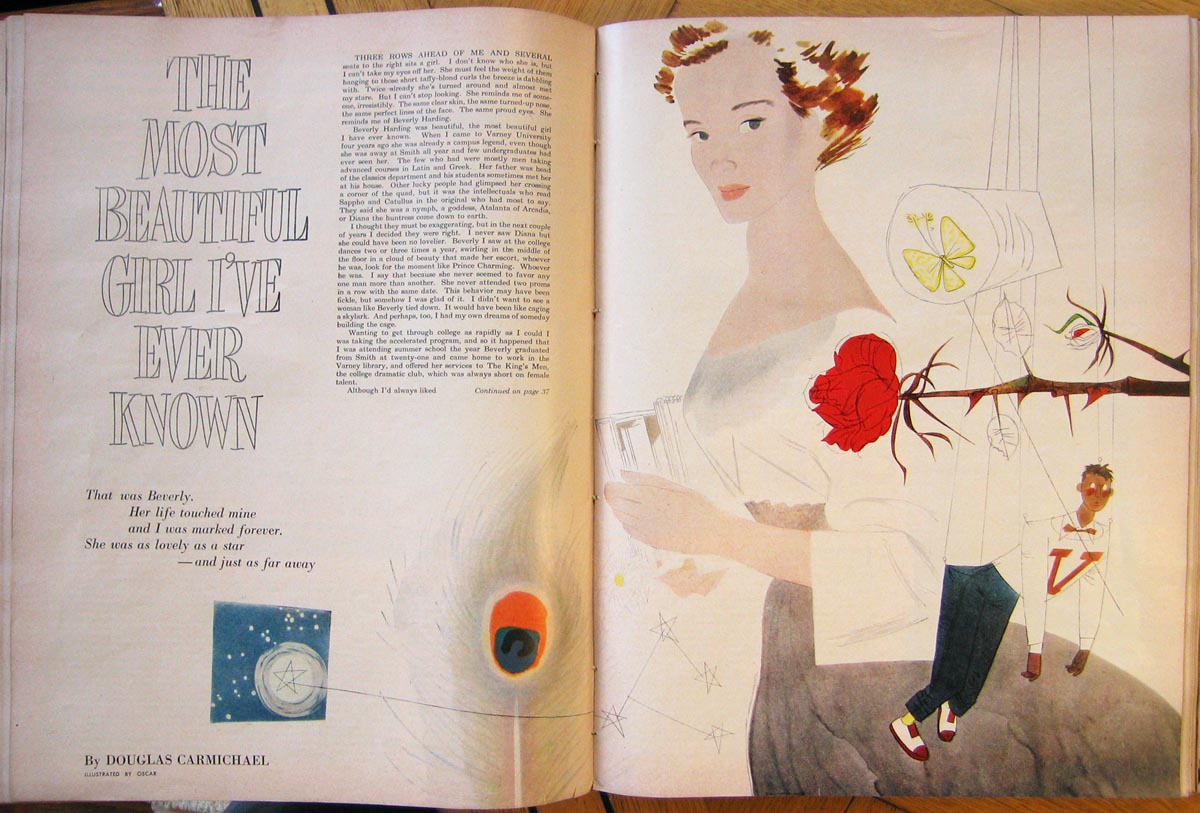

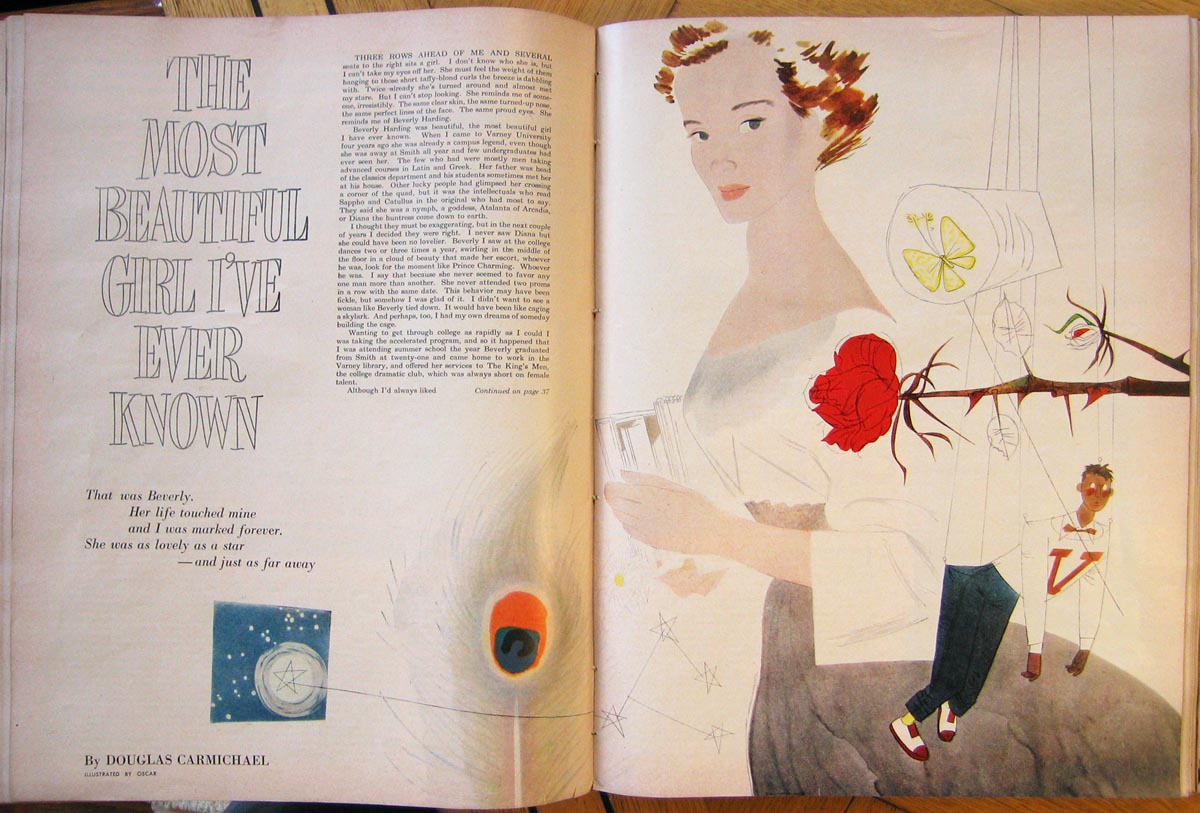

Fiction illustration for “A Cage for the Bird Man,” Maclean’s, 1954.

“There isn’t any doubt that Oscar Cahén was the greatest single force in Canadian illustration since [Charles W] Jefferys.”

Fiction illustration for “A Cage for the Bird Man,” Maclean’s, 1954.

“There isn’t any doubt that Oscar Cahén was the greatest single force in Canadian illustration since [Charles W] Jefferys.”

In 1959, these were the words of Stan Furnival, art director at

Maclean’s Magazine. He published some of Oscar Cahén’s best illustration, until Cahén’s untimely death at age 40 in 1956. The first exhibition of Oscar Cahén’s illustration

since his lifetime will be shown in New York at Illustration House in October 2011 (opening night Oct. 1). With Roger Reed, I have written a full colour catalogue with an essay and over 60 images. In this series of posts about Cahén, I will introduce him and feature some artwork that will not appear in the show, catalogue, or websites. The tearsheets and originals here are from Oscar Cahén’s estate, courtesy of his son Michael Cahén at The Cahén Archives.

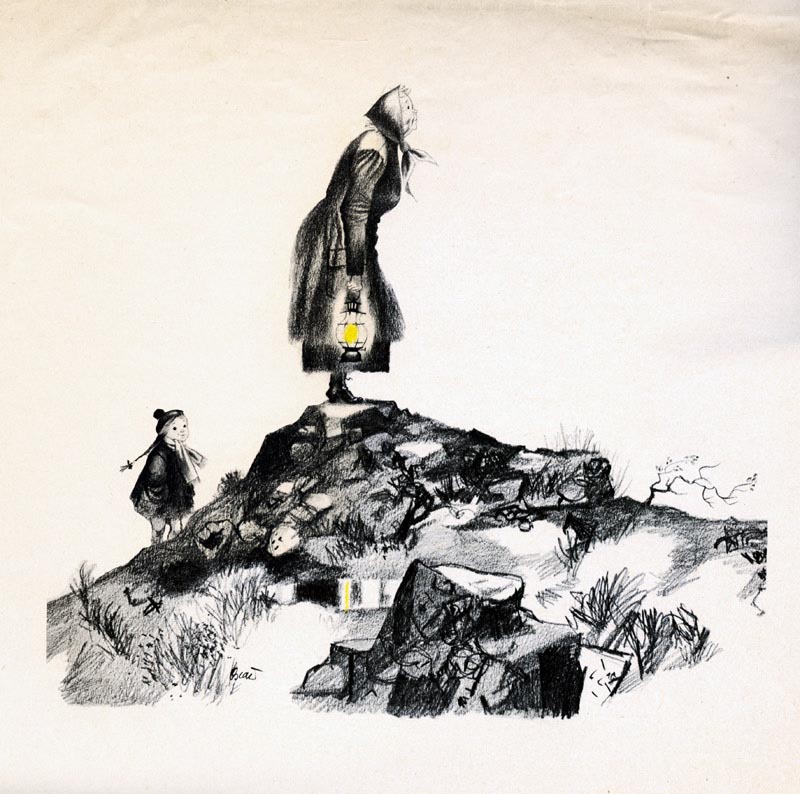

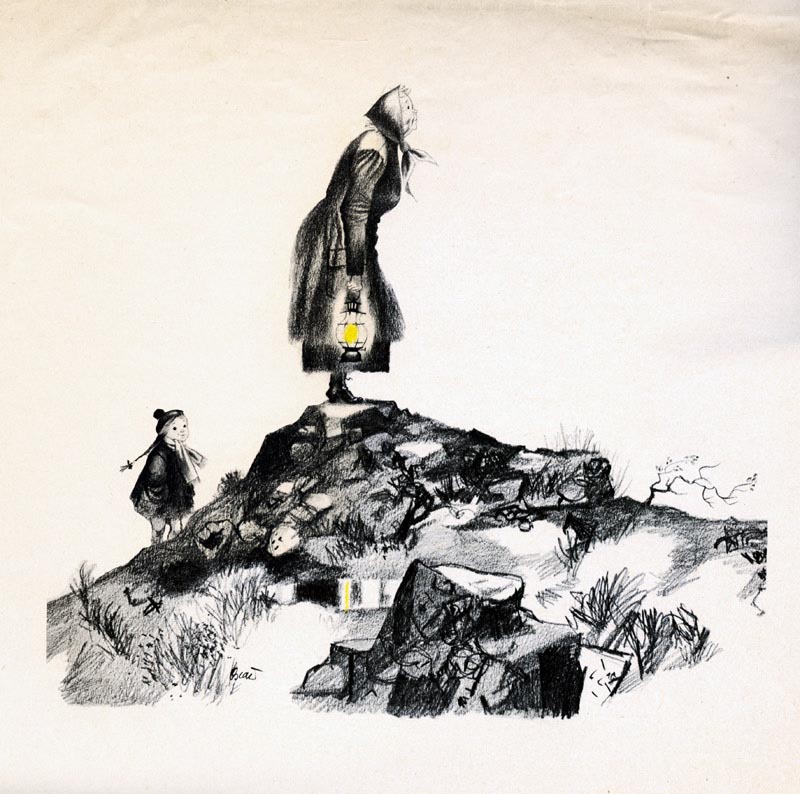

Fiction illustration for “Hayaqwus and the Cross,” The Standard.

Fiction illustration for “Hayaqwus and the Cross,” The Standard.

Oscar Cahén had already completed a mature body of work as an illustrator, and had established a national reputation as an abstract painter as well. His Canadian work kept him so busy he never had time to pursue contracts in the United States, but if he had, we might have been discussing him in the same breath as Harry Beckhoff, Al Parker, David Stone Martin, Saul Steinberg, Robert Weaver, or Bob Peak. Each of these illustrators were very different from one another, but Cahén managed to cover the entire range they represent from cartoon to boy-girl to line drawing to robust painterliness to conceptual illustration to abstraction. If his annual harvests of awards from the Art Directors Club of Toronto are any indication, his peers thought he did it all superbly.

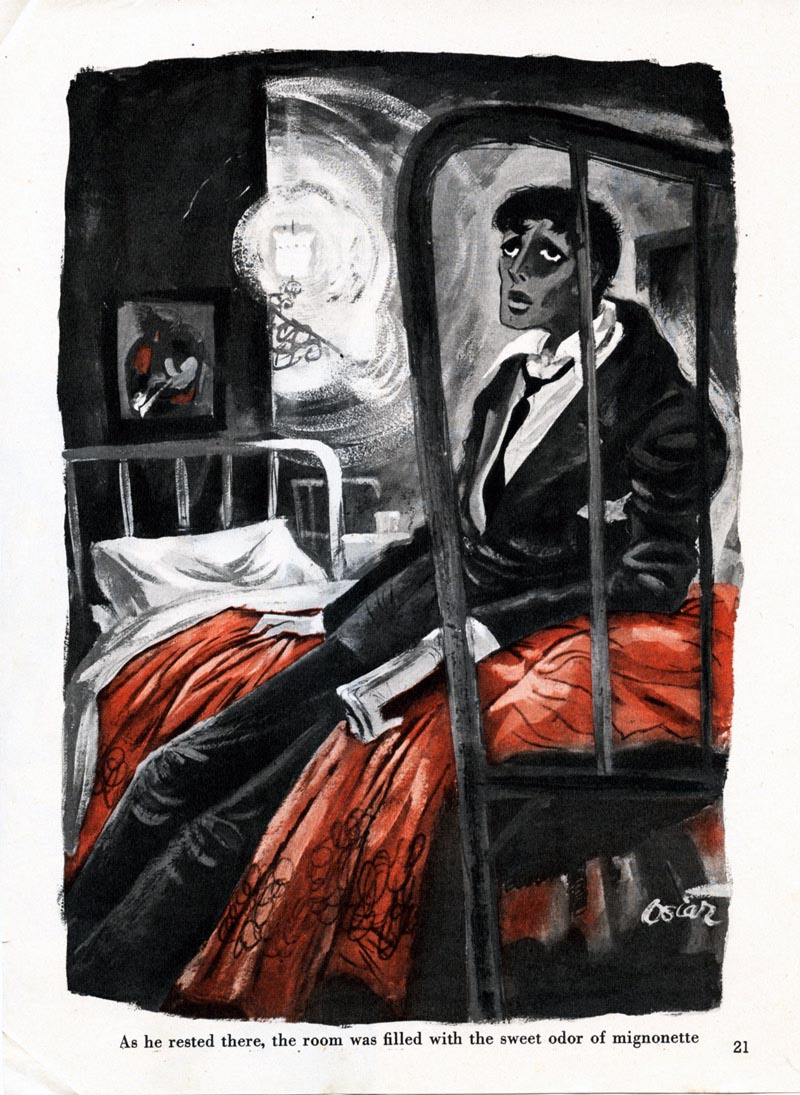

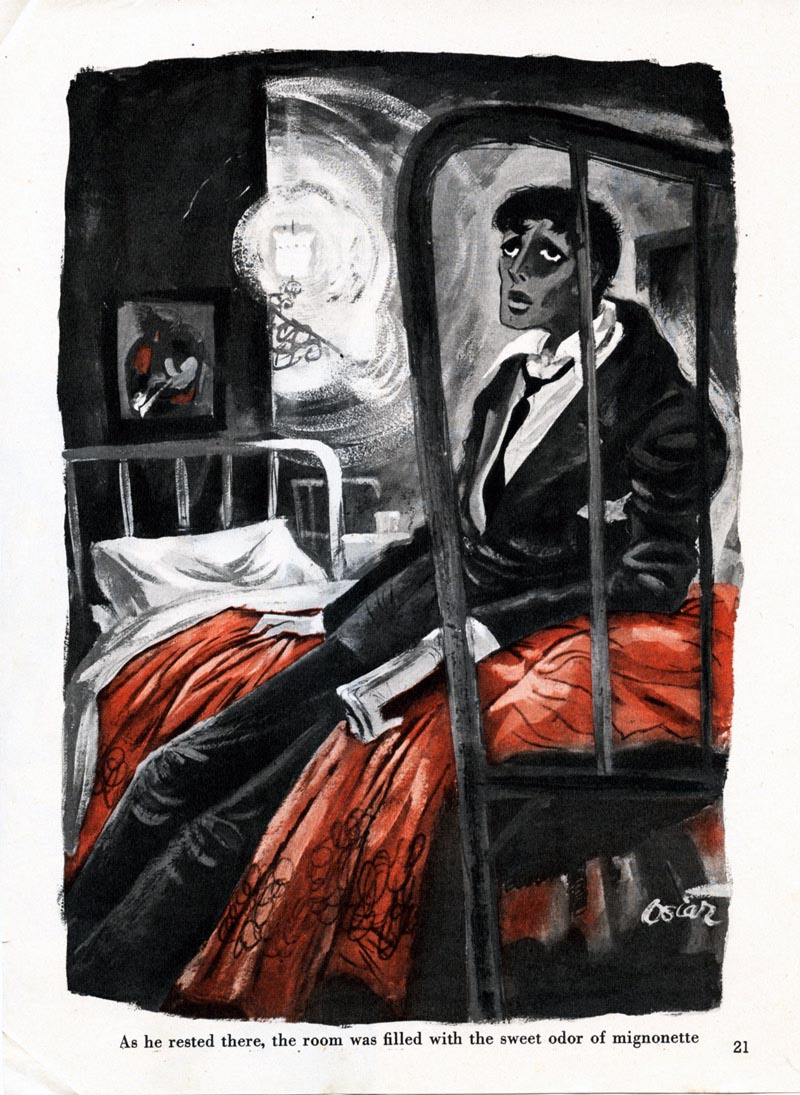

Award winning fiction illustration for Maclean’s.

Award winning fiction illustration for Maclean’s.

We don’t know where this image appeared. If you do, contact The Cahén Archives.

We don’t know where this image appeared. If you do, contact The Cahén Archives.

Oscar Cahén’s life was dramatic from start to finish. Falsifying his birth certificate, at 14 (1930) he entered the Dresden Kunstakademie, a venerable institution whose alumni included dadaist Kurt Schwitters and caricaturist-painter Georg Grosz. He was practicing professionally by 18. In 1934, Cahén showed 79 works of advertising illustration, landscapes, and portraits in Prague and in Copenhagen. Youthful Cahén declared Surrealism “contains a lot of good things” and that the purpose of art was “bringing things into the light.”

We don’t know where this image appeared. If you do, contact The Cahén Archives.

We don’t know where this image appeared. If you do, contact The Cahén Archives.

In 1940 he came to Canada from Europe at age 24, as a prisoner of war. His father Fritz Max Cahén was a Jewish political journalist and ex-diplomat who was organizing resistance against the Nazis, but when Oscar fled to England, he was held because he had German citizenship. He was subsequently interned near Sherbrooke, Quebec, and he began his Canadian illustration career while still behind barbed wire, completing assignments for Montreal’s

The Standard.

Oscar Cahén was to Canadian illustration what the similarly outspoken Robert Weaver was to American illustration, unapologetic about being an illustrator and critical of illustration at the same time (except he didn’t make enemies, as Weaver did!).

In an essay printed in the 1954 Annual of the Art Directors Club of Toronto, Cahén said:

"It is fine for the modern Art Director of a publication to think of the "Public" as long as it does not completely dominate the approach to his work . . . Of all the professional visual arts, Editorial Illustration is one of the few which offers truly great opportunity for creative work, and it is unfortunate that few Art Directors realize the potential power of their position, namely, the opportunity to contribute actively towards the cultural development of our society."

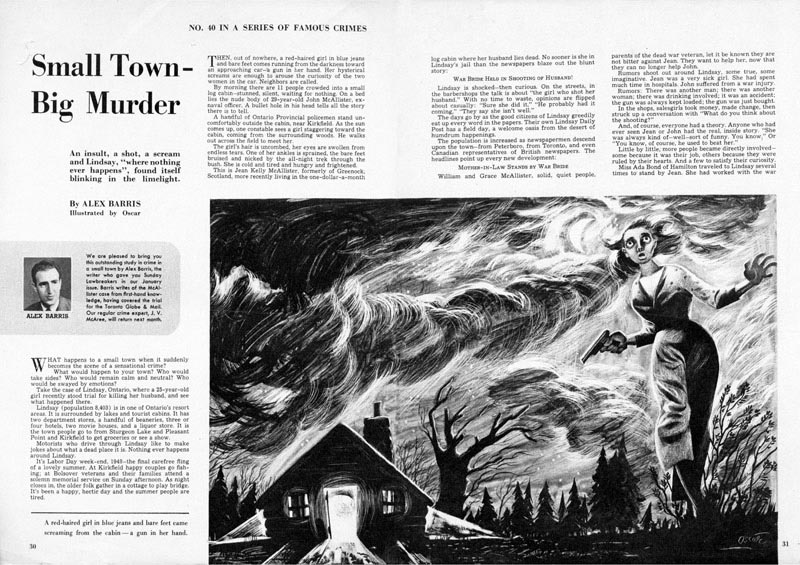

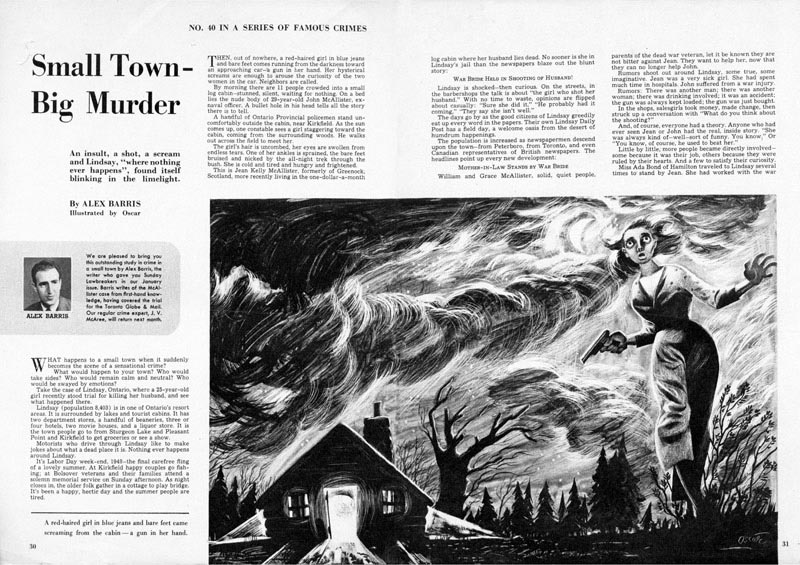

New Liberty, 1949.

New Liberty, 1949.

Cahén also iterated what he felt was of merit in illustration: “a degree of individuality,” something “transmitting emotions beyond the representational value therein” in order to influence the viewer, “emotional and story-telling values,” and the use of “what is called ‘Fine Art’” where appropriate. Oscar Cahén indisputably lived up to his own advice.

* Continued tomorrow...

Fiction illustration for “A Cage for the Bird Man,” Maclean’s, 1954.

Fiction illustration for “A Cage for the Bird Man,” Maclean’s, 1954.

How could you not mention Hurst, Dorne and Searle? Clear influences.

ReplyDeleteGreat stuff.

...or Shahn, or Reid, for that matter. The catalog says more than this blog will. I considered Searle, but ended up not mentioning him because I haven't looked into when Searle's work started being seen - he was in a prison camp in Asia as I recall, when Oscar was already publishing in Canada. Len Norris is prob a bridge between them. There's really much much more work to do - I hope people will cut me the slack that I only had about a month to research and write. It's just the beginning! Thanks for mentioning Hurst; I'll look into that.

ReplyDeleteI think you do a wonderful job. I've never seen a lot of what you dig up. So I'm always pleased to see your twitter. Oohh! Pardon.

ReplyDeleteMore talented than Weaver.

ReplyDeleteFortunate indeed is the illustrator who has Jaleen Grove as his or her biographer!

ReplyDeleteI love classic illustrations and pics!

ReplyDelete